Sam was a Russian Jew that came to America when he was three years old with his family. His father was trying to escape the draft. He began working in a textile mill at 13 years old. As Sam got older he began speaking up about the horrible working conditions employees faced in the factories and mills. He worked for many companies including: After Six, The Spector Brothers, and N. Snellenberg & Company. He joined unions and stood up to his bosses. His association with the union and with outspoken political opinions made employers hesitant to hire him. Sam was a rebel. He stood up for what he knew was right and used his voice to in attempt to empower others.

Sam Brosilow был русским евреем, который приехал в Америку, когда ему было три года со своей семьей.

“I admit, I’m a rebel. I’ve always been a rebel. I’ve never taken anything for granted. Everything had to have certain reasons, and certain whys and wherefores, and if they didn’t satisfy me I wouldn’t have it. Now, that’s the best I can give you.” – Sam Brosilow, 1981

Family.

In 1931 Sam married Ethel Stein. He met Ethel in a union. They had one son together. Despite Sam’s father being illiterate and Sam himself never attending high school, his son Coleman got his Ph.D. at the Polytechnic Institute of New York. He went on to teach chemical engineering at Case Western University in Cleveland for almost forty years. This proves that nothing is impossible and that hard work pays off in the end.

Sam talks about when his family moved into a new development in Philadelphia due to a business opportunity.

“We were looking for a new place… my mother and dad were looking for a new place for a new business, so they went up there where they were recommended. It was a new development. My mother walked into there and she saw a tile bathroom and a regular hopper, that was it. There were no electric lights only gas so, my mother wouldn’t walk out of there. “You must buy it” she said to my father. *laughs* So, he bought it. We stayed there for past thirty years. So, Philadelphia changed for me again.”

Unionism/ Philadelphia General Strike of 1910.

Sam describes when he witnessed his first labor strike, how it made him feel, and how it impacted his future.

“They had trollies running, the open-air trollies, and I saw my first labor strike in front of our house, and I came running home. I was excited. I said, “There’s a lot of people being hurt and being arrested” my mother and father said, “don’t worry everything is okay; they’re strikers and the police are taking care of them”. So, I said “okay”. It was the Pennsylvania state police, they used to be called the Cossacks of Pennsylvania. Well, they were the employees of the Rapid Transmit Company and they were on strike. The first strike that I ever saw although I would go on to participate in plenty of them. That was the first one that I ever saw. And that’s where they left an impression on me that I have never forgotten.”

Watch this YouTube video to learn more about unions.

Child Labor and Sam’s first job.

Sam recalls his first job in a textile mill. He shares the responsibilities he had as a bobbing boy along with the unsafe conditions he worked in.

“Q: When you were a kid you worked in a textile mill. S: Well, that was before the twenties. That was in the teens. I was fourteen years old by 1911. So, during this summer I decided that I was going to be a big shot. I was going to earn some money. I went to earn money and I got a fabulous salary. I don’t remember if it was $5 a week or $7 a week. So, I was a bobbing boy. Now the bobbing boy did nothing more or less. They had taken the lint and wove it into thread. Then they took the thread and put it on a huge cone. Now, why they did that I don’t know. But then what they did after that was, they put the cones in a machine, and they had a smaller cone that they used for one to the other. The thread used to go around it and I used to have to go along and mend the thread as it broke. Without any air in the place, damp and that was it! And as I said before I don’t even remember what I was getting paid. I couldn’t have gotten very much even by those standards.”

Sam describes his job as a spindle boy and contrasts the working conditions in the different mills and factories during that time.

“Q: Among the cutter and the tailors in the teens and the twenties was there a great dissatisfaction with their employment conditions? S: Yes. Yes… Q: Because I have heard varying stories and I have talked to a lot of people who worked in the mills… S: The mills are different. Q: Okay, how is that? S: Because conditions were different. Now don’t confuse the woolen mills and the cotton mills from the men’s clothing industry. Because of the fact that you have different labor conditions. Q: How would you contrast them? S: Well, they got what they called brown lung. It came about from the constant lint. Q: This is in the mills? S: In the mills of the cloth. I’ll give an illustration when I was still going to grammar school, one summer I decided to go to work. So, where did I go to work? I went to Wilson Home, a very big cotton producer. What I mean… sewing cottons. All people had to sew. So, I went up there and I got a job as a spindle boy. Well, what is a spindle boy? It’s more or less checking the materials, the thread, on a huge cone and putting it on a smaller cone to use in the various needle industries. You know you weren’t allowed to open a window there? Q: Why? S: Because the breeze would break the threads. My job was to watch all the spindles while they were running and if any of them broke, I was to run over, take the lose ends, twist them in my wet fingers, then just once around, and that’s it. Q: How old were you then when you started working in the mills? S: I was about thirteen years old. Q: Were there a lot of kids in the mills then? S: More than there would normally be because the working age was changed after.”

Who was Mother Jones? Watch this video to find out.

Education.

Sam describes how the value and philosophy of education has changed overtime.

“I started working when I graduated grammar school. My father wouldn’t send me to high school. Q: Why not? S: He didn’t believe in education. Now if you must remember that my father never had a day of schooling in Russia. So, if I knew how to read and write and tell him how to sign his name then I knew more than he did. So, why did I have to go to high school? He said, “I want you to learn a trade”. Now this is the philosophy of the people that has changed as well as the city. If you’ve got a trade, you’ll always make a living. So, what does that mean? What do you need college for? What do you need high school for? Why do you need universities? That was the common philosophy of the immigrants that came in the period between 1899 and 1920s. Q: What did your father think about you going to work in the mill that summer? S: He didn’t care! As a matter of fact, he didn’t even want me to go to high school! Now this sounds strange, but he came from Europe and he was illiterate himself. He didn’t know how to read or write anything! But there’s a reason for that, His mother was a widow. He was the oldest of the group, so she sold him… she put him into an apprenticeship to a tailor. And when you do that in Russia or in the old country or any country it didn’t make any difference, you were a virtual slave. And that how he spent his youth.”

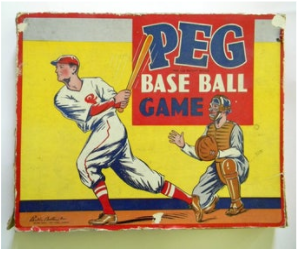

Baseball.

Sam shares his favorite hobby growing up, peg baseball, and recalls going to see baseball games twice a week to deliver the uniforms to each team.

“Q: How often did you go to a baseball game? S: Without any exaggeration, I don’t have the exact count but thinking back it must’ve been at least twice a week. Sometimes more, sometimes less. But on average twice a week. I got so damn tired of the game I didn’t even want to see it anymore. Q: Would you go on your own? Would the other kids come up? S: I went with a group, yeah. We would take the suits in and walk by nobody ever stopped you. Q: And do what? S: And walk right by the door keepers. We would say, “We have to take this and deliver it to them” and they would say “Oh okay!” They knew what was going on, but they didn’t want to stop us. I wouldn’t sneak in, no if that’s what you meant. Q: What do you mean you would take the suits in? S: I would have to deliver the suits to the clubhouse. Q: So, your father actually did pressing for the clubs? S: Yes. He did it for the visitors and the clubs. You know, after all at any stage of the game an athlete always made some extra money. So, we had an extra buck to spend. So, the extra buck went to looking good in his clothes. That’s all he had to look forward to. So, there’s your answer. Q: So, your father got the business from these guys? S: No, he didn’t get it. Somebody came in and asked him to take the business because he was the only one around there. Q: Was baseball a big sport? S: Baseball was always a big sport. Well, I recall there was a team called the Oxford team. So, they had a ballpark there and that was the first that I heard about it. I never saw it but of course I wasn’t that interested in the sport. I was too young to understand what it meant. But it was always a big sport especially with kids. We just played ball in the street. I was once asked by a group of children “What was I doing when I was a youngster? What was my favorite game?” So, I said, “Peg baseball”. You know what peg baseball meant? Q: Is it like stick ball? S: Right but, no more than that. It meant that you used a thicker wood, a small stick of wood. And then you would take a longer piece of wood and whack that on the curb and see how long it would go.”